This document assumes you have already installed Python 3, and you have used both pip and venv. If not, refer to these instructions.

22 hours ago You Cannot Miss These 8 Python Libraries analyticsvidhya.com - kaustubh1828. 13h. Crowd funding is over !!emv software. ArticleVideo Book This article was published as a part of the Data Science Blogathon. Ultimately I hope to show you some tricks and tips to make web scraping less overwhelming. Installing our dependencies. All the resources from this guide are available at my GitHub repo. If you need help installing Python 3, check out the tutorials for Linux, Windows, and Mac.

Sweigart briefly covers scraping in chapter 12 of Automate the Boring Stuff with Python (second edition).

This chapter here and the two following chapters provide additional context and examples for beginners.

BeautifulSoup documentation:

Setup for BeautifulSoup¶

BeautifulSoup is a scraping library for Python. We want to run all our scraping projects in a virtual environment, so we will set that up first. (Students have already installed Python 3.)

Create a directory and change into it¶

The first step is to create a new folder (directory) for all your scraping projects. Mine is:

Do not use any spaces in your folder names. If you must use punctuation, do not use anything other than an underscore _. It’s best if you use only lowercase letters.

Change into that directory. For me, the command would be:

Create a new virtualenv in that directory and activate it¶

Create a new virtual environment there (this is done only once).

MacOS:

Windows:

Activate the virtual environment:

MacOS:

Windows:

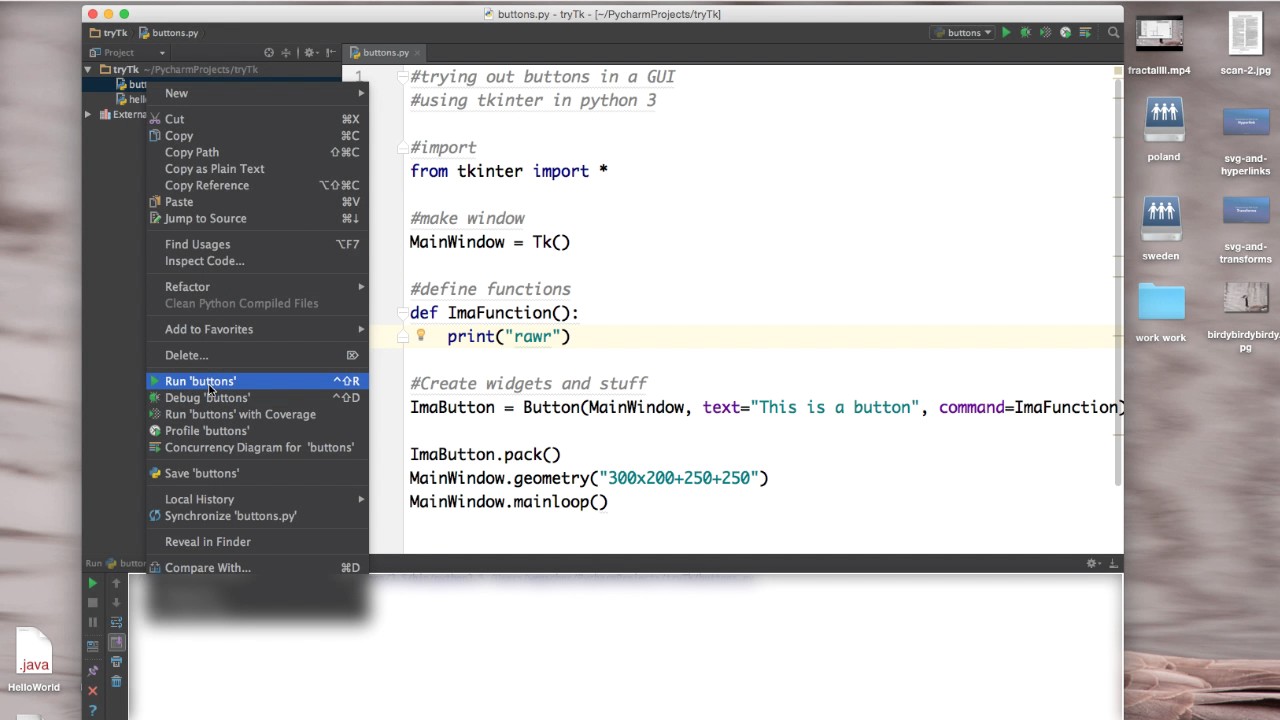

Important: You should now see (env) at the far left side of your prompt. This indicates that the virtual environment is active. For example (MacOS):

When you are finished working in a virtual environment, you should deactivate it. The command is the same in MacOS or Windows (DO NOT DO THIS NOW):

You’ll know it worked because (env) will no longer be at the far left side of your prompt.

Install the BeautifulSoup library¶

In MacOS or Windows, at the command prompt, type:

This is how you install any Python library that exists in the Python Package Index. Pretty handy. pip is a tool for installing Python packages, which is what you just did.

Note

You have installed BeautifulSoup in the Python virtual environment that is currently active. Download free webbased chat program. When that virtual environment is not active, BeautifulSoup will not be available to you. This is ideal, because you will create different virtual environments for different Python projects, and you won’t need to worry about updated libraries in the future breaking your (past) code.

Test BeautifulSoup¶

Start Python. Because you are already in a Python 3 virtual environment, Mac users need only type python (NOT python3). Windows users also type python as usual.

You should now be at the >>> prompt — the Python interactive shell prompt.

In MacOS or Windows, type (or copy/paste) one line at a time:

You imported two Python modules,

urlopenandBeautifulSoup(the first two lines).You used

urlopento copy the entire contents of the URL given into a new Python variable,page(line 3).You used the

BeautifulSoupfunction to process the value of that variable (the plain-text contents of the file at that URL) through a built-in HTML parser calledhtml.parser.The result: All the HTML from the file is now in a BeautifulSoup object with the new Python variable name

soup. (It is just a variable name.)Last line: Using the syntax of the BeautifulSoup library, you printed the first

h1element (including its tags) from that parsed value.

If it works, you’ll see:

Check out the page on the web to see what you scraped.

Attention

If you got an error about SSL, quit Python (quit() or Command-D) and COPY/PASTE this at the command prompt (MacOS only):

Then return to the Python prompt and retry the five lines above.

The command soup.h1 would work the same way for any HTML tag (if it exists in the file). Instead of printing it, you might stash it in a variable:

Then, to see the text in the element without the tags:

Understanding BeautifulSoup¶

BeautifulSoup is a Python library that enables us to extract information from web pages and even entire websites.

We use BeautifulSoup commands to create a well-structured data object (more about objects below) from which we can extract, for example, everything with an <li> tag, or everything with class='book-title'.

After extracting the desired information, we can use other Python commands (and libraries) to write the data into a database, CSV file, or other usable format — and then we can search it, sort it, etc.

What is the BeautifulSoup object?¶

It’s important to understand that many of the BeautifulSoup commands work on an object, which is not the same as a simple string.

Many programming languages include objects as a data type. Python does, JavaScript does, etc. An object is an even more powerful and complex data type than an array (JavaScript) or a list (Python) and can contain many other data types in a structured format.

When you extract information from an object with a BeautifulSoup command, sometimes you get a single Tag object, and sometimes you get a Python list (similar to an array in JavaScript) of Tag objects. The way you treat that extracted information will be different depending on whether it is one item or a list (usually, but not always, containing more than one item).

That last paragraph is REALLY IMPORTANT, so read it again. For example, you cannot call .text on a list. You’ll see an error if you try it.

How BeautifulSoup handles the object¶

In the previous code, when this line ran:

… you copied the entire contents of a file into a new Python variable named page. The contents were stored as an HTTPResponse object. We can read the contents of that object like this:

… but that’s not going to be very usable, or useful — especially for a file with a lot more content in it.

When you transform that HTTPResponse object into a BeautifulSoup object — with the following line — you create a well-structured object from which you can extract any HTML element and the text and/or attributes within any HTML element.

Some basic BeautifulSoup commands¶

Let’s look at a few examples of what BeautifulSoup can do.

Finding elements that have a particular class¶

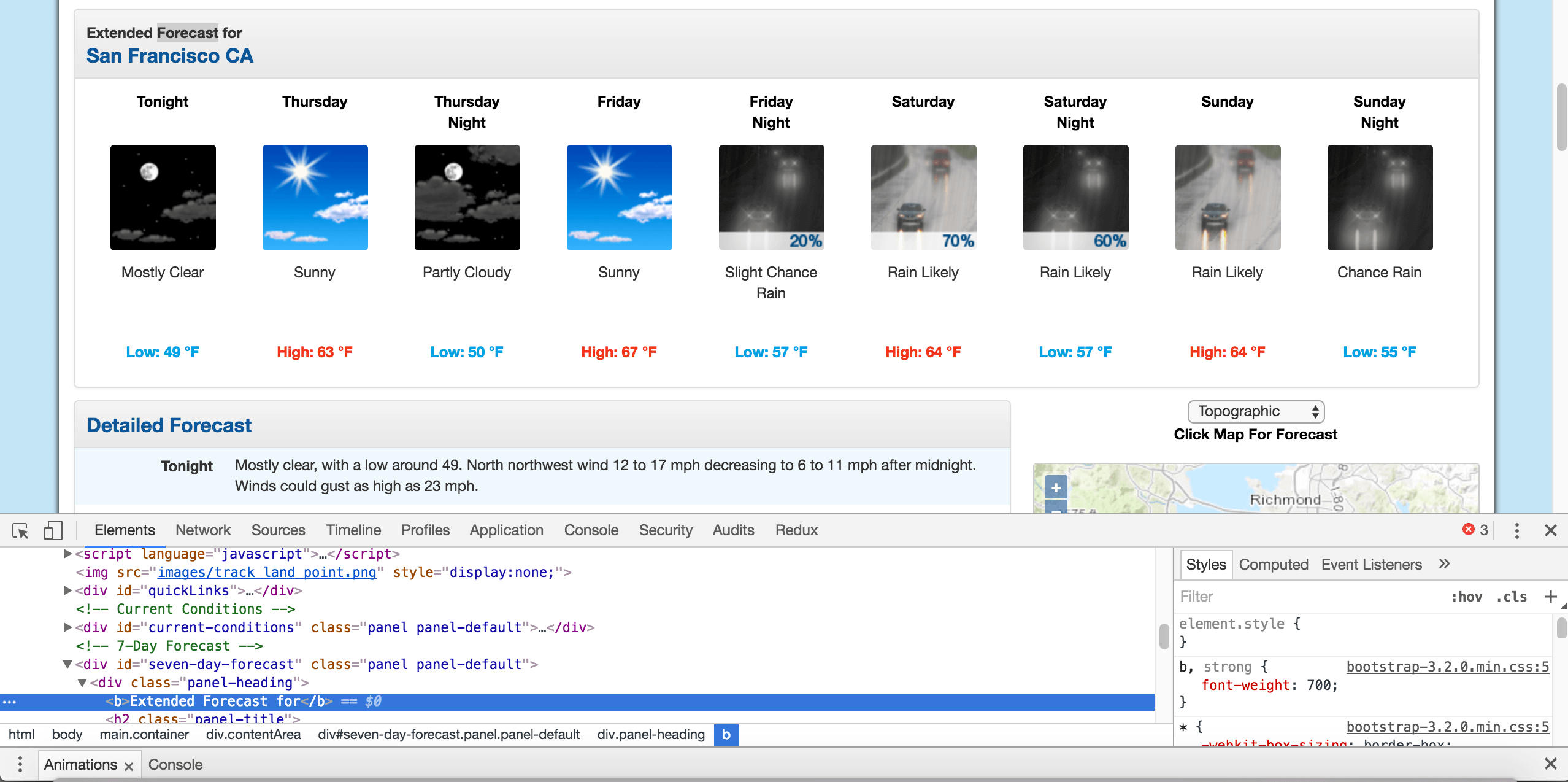

Deciding the best way to extract what you want from a large HTML file requires you to dig around in the source, using Developer Tools, before you write the Python/BeautifulSoup commands. In many cases, you’ll see that everything you want has the same CSS class on it. After creating a BeautifulSoup object (here, as before, it is soup), this line will create a Python list containing all the <td> elements that have the class city.

Attention

The word class is a reserved word in Python. Using class (alone) in the code above would give you a syntax error. So when we search by CSS class with BeautifulSoup, we use the keyword argument class_ — note the added underscore. Other HTML attributes DO NOT need the underscore.

Maybe there were 10 cities in <td> tags in that HTML file. Maybe there were 10,000. No matter how many, they are now in a list (assigned to the variable city_list), and you can search them, print them, write them out to a database or a JSON file — whatever you like. Often you will want to perform the same actions on each item in the list, so you will use a normal Python for-loop:

.get_text() is a handy BeautifulSoup method that will extract the text — and only the text — from the Tag object. If instead you wrote just print(city), you’d get the complete <td> — and any other tags inside that as well.

Note

The BeautifulSoup methods .get_text() and .getText() are the same. The BeautifulSoup property .text is a shortcut to .get_text() and is acceptable unless you need to pass arguments to .get_text().

Finding all vs. finding one¶

The BeautifulSoup find_all() method you just saw always produces a list. (Note: findAll() will also work.) If you know there will be only one item of the kind you want in a file, you should use the find() method instead.

For example, maybe you are scraping the address and phone number from every page in a large website. In this case, there is only one phone number on the page, and it is enclosed in a pair of tags with the attribute id='call'. One line of your code gets the phone number from the current page:

You don’t need to loop through that result — the variable phone_number will contain only one Tag object, for whichever HTML tag had that ID. To test what the text alone will look like, just print it using get_text() to strip out the tags.

Notice that you’re often using soup. Review above if you’ve forgotten where that came from. (You may use another variable name instead, but soup is the usual choice.)

Finding the contents of a particular attribute¶

One last example from the example page we have been using.

Say you’ve made a BeautifulSoup object from a page that has dozens of images on it. You want to capture the path to each image file on that page (perhaps so that you can download all the images). I would do this in two steps:

First, you make a Python list containing all the

imgelements that exist in thesoupobject.Second, you loop through that list and print the contents of the

srcattribute from eachimgtag in the list.

It is possible to condense that code and do the task in two lines, or even one line, but for beginners it is clearer to get the list of elements and name it, then use the named list and get what is wanted from it.

Important

We do not need get_text() in this case, because the contents of the src attribute (or any HTML attribute) are nothing but text. There are never tags inside the src attribute. So think about exactly what you’re trying to get, and what is it like inside the HTML of the page.

You can see the code from above all in one file.

There’s a lot more to learn about BeautifulSoup, and we’ll be working with various examples. You can always read the docs. Most of what we do with BeautifulSoup, though, involves these tasks:

Find everything with a particular class

Find everything with a particular attribute

Find everything with a particular HTML tag

Find one thing on a page, often using its

idattributeFind one thing that’s inside another thing

A BeautifulSoup scraping example¶

To demonstrate the process of thinking through a small scraping project, I made a Jupyter Notebook that shows how I broke down the problem step by step, and tested one thing at a time, to reach the solution I wanted. Open the notebook here on GitHub to follow along and see all the steps. (If that link doesn’t work, try this instead.)

Web Scraping Scrapy Python 3

The code in the final cell of the notebook produces this 51-line CSV file by scraping 10 separate web pages.

To run the notebook, you will need to have installed the Requests module and also Jupyter Notebook.

See these instructions for information about how to run Jupyter Notebooks.

Attention

After this introduction, you should NOT use fromurllib.requestimporturlopen or the urlopen() function. Instead, you will use requests as demonstrated in the notebook linked above.

Next steps¶

In the next chapter, we’ll look at how to handle common web scraping projects with BeautifulSoup and Requests.

.

Someone on the NICAR-L listserv asked for advice on the best Python libraries for web scraping. My advice below includes what I did for last spring’s Computational Journalism class, specifically, the Search-Script-Scrape project, which involved 101-web-scraping exercises in Python.

See the repo here: https://github.com/compjour/search-script-scrape

Best Python libraries for web scraping

For the remainder of this post, I assume you’re using Python 3.x, though the code examples will be virtually the same for 2.x. For my class last year, I had everyone install the Anaconda Python distribution, which comes with all the libraries needed to complete the Search-Script-Scrape exercises, including the ones mentioned specifically below:

The best package for general web requests, such as downloading a file or submitting a POST request to a form, is the simply-named requests library(“HTTP for Humans”).

Here’s an overly verbose example:

The requests library even does JSON parsing if you use it to fetch JSON files. Here’s an example with the Google Geocoding API:

For the parsing of HTML and XML, Beautiful Soup 4 seems to be the most frequently recommended. I never got around to using it because it was malfunctioning on my particular installation of Anaconda on OS X.

But I’ve found lxml to be perfectly fine. I believe both lxml and bs4 have similar capabilities – you can even specify lxml to be the parser for bs4. I think bs4 might have a friendlier syntax, but again, I don’t know, as I’ve gotten by with lxml just fine:

The standard urllib package also has a lot of useful utilities – I frequently use the methods from urllib.parse. Python 2 also has urllib but the methods are arranged differently.

Here’s an example of using the urljoin method to resolve the relative links on the California state data for high school test scores. The use of os.path.basename is simply for saving the each spreadsheet to your local hard drive:

And that’s about all you need for the majority of web-scraping work – at least the part that involves reading HTML and downloading files.

Examples of sites to scrape

The 101 scraping exercises didn’t go so great, as I didn’t give enough specifics about what the exact answers should be (e.g. round the numbers? Use complete sentences?) or even where the data files actually were – as it so happens, not everyone Googles things the same way I do. And I should’ve made them do it on a weekly basis, rather than waiting till the end of the quarter to try to cram them in before finals week.

The Github repo lists each exercise with the solution code, the relevant URL, and the number of lines in the solution code.

The exercises run the gamut of simple parsing of static HTML, to inspecting AJAX-heavy sites in which knowledge of the network panel is required to discover the JSON files to grab. In many of these exercises, the HTML-parsing is the trivial part – just a few lines to parse the HTML to dynamically find the URL for the zip or Excel file to download (via requests)…and then 40 to 50 lines of unzipping/reading/filtering to get the answer. That part is beyond what typically considered “web-scraping” and falls more into “data wrangling”.

I didn’t sort the exercises on the list by difficulty, and many of the solutions are not particulary great code. Sometimes I wrote the solution as if I were teaching it to a beginner. But other times I solved the problem using the style in the most randomly bizarre way relative to how I would normally solve it – hey, writing 100+ scrapers gets boring.

But here are a few representative exercises with some explanation:

1. Number of datasets currently listed on data.gov

I think data.gov actually has an API, but this script relies on finding the easiest tag to grab from the front page and extracting the text, i.e. the 186,569 from the text string, '186,569 datasets found'. This is obviously not a very robust script, as it will break when data.gov is redesigned. Download aplikasi converter video mp4 ke avimarcus reid. But it serves as a quick and easy HTML-parsing example.

29. Number of days until Texas’s next scheduled execution

Texas’s death penalty site is probably one of the best places to practice web scraping, as the HTML is pretty straightforward on the main landing pages (there are several, for scheduled and past executions, and current inmate roster), which have enough interesting tabular data to collect. But you can make it more complex by traversing the links to collect inmate data, mugshots, and final words. This script just finds the first person on the scheduled list and does some math to print the number of days until the execution (I probably made the datetime handling more convoluted than it needs to be in the provided solution)

3. The number of people who visited a U.S. government website using Internet Explorer 6.0 in the last 90 days

The analytics.usa.gov site is a great place to practice AJAX-data scraping. It’s a very simple and robust site, but either you are aware of AJAX and know how to use the network panel (and in this case, locate ie.json, or you will have no clue how to scrape even a single number on this webpage. I think the difference between static HTML and AJAX sites is one of the tougher things to teach novices. But they pretty much have to learn the difference given how many of today’s websites use both static and dynamically-rendered pages.

6. From 2010 to 2013, the change in median cost of health, dental, and vision coverage for California city employees

Web Scraping In Python 3 Example

There’s actually no HTML parsing if you assume the URLs for the data files can be hard coded. So besides the nominal use of the requests library, this ends up being a data-wrangling exercise: download two specific zip files, unzip them, read the CSV files, filter the dictionaries, then do some math.

90. The currently serving U.S. congressmember with the most Twitter followers

Another example with no HTML parsing, but probably the most complicated example. You have to download and parse Sunlight Foundation’s CSV of Congressmember data to get all the Twitter usernames. Then authenticate with Twitter’s API, then perform mulitple batch lookups to get the data for all 500+ of the Congressional Twitter usernames. Then join the sorted result with the actual Congressmember identity. I probably shouldn’t have assigned this one.

HTML is not necessary

I included no-HTML exercises because there are plenty of data programming exercises that don’t have to deal with the specific nitty-gritty of the Web, such as understanding HTTP and/or HTML. It’s not just that a lot of public data has moved to JSON (e.g. the FEC API) – but that much of the best public data is found in bulk CSV and database files. These files can be programmatically fetched with simple usage of the requests library.

It’s not that parsing HTML isn’t a whole boatload of fun – and being able to do so is a useful skill if you want to build websites. But I believe novices have more than enough to learn from in sorting/filtering dictionaries and lists without worrying about learning how a website works.

Besides analytics.usa.gov, the data.usajobs.gov API, which lists federal job openings, is a great one to explore, because its data structure is simple and the site is robust. Here’s a Python exercise with the USAJobs API; and here’s one in Bash.

There’s also the Google Maps geocoding API, which can be hit up for a bit before you run into rate limits, and you get the bonus of teaching geocoding concepts. The NYTimes API requires creating an account, but you not only get good APIs for some political data, but for content data (i.e. articles, bestselling books) that is interesting fodder for journalism-related analysis.

But if you want to scrape HTML, then the Texas death penalty pages are the way to go, because of the simplicity of the HTML and the numerous ways you can traverse the pages and collect interesting data points. Besides the previously mentioned Texas Python scraping exercise, here’s one for Florida’s list of executions. And here’s a Bash exercise that scrapes data from Texas, Florida, and California and does a simple demographic analysis.

If you want more interesting public datasets – most of which require only a minimal of HTML-parsing to fetch – check out the list I talked about in last week’s info session on Stanford’s Computational Journalism Lab.